First introduced at Apple’s Worldwide Developers Conference (WWDC) in June 2020, the iOS 14 privacy labels finally went online at the end of the year. Like a nutrition label on food packages, these labels are now a requirement for developers who want to sell iOS, iPadOS, tvOS, watchOS, and macOS apps. Developers must maintain accurate labels and make necessary changes whenever they submit an app update. For a level playing field, Apple is also providing App Store privacy labels for its apps. Native apps that don’t have a place in the App Store also have privacy labels. For example, you can find the label for the Messages app on the Apple Support site.

App Store Privacy Labels: The Details

At launch, the new labels come divided into three categories: “data used to track you,” “data linked to you,” and “data not linked to you.”

Data Used to Track You

Under data tracking, a developer needs to disclose whether it’s providing personal information or data collected from a user’s device to a third-party. This stakeholder could be another company or website that uses the data for targeted advertising. Tracking here also refers to sharing user or device information with companies like data brokers that sell user data to other entities. Apple explains: Two areas where Apple doesn’t consider tracking are: when data is linked solely on a device and is not sent off the device in a way that can identify the end-user or device; and when a data broker uses the data shared solely for fraud detection or prevention or security purposes. “Third-Party Data” refers to any data about a particular end-user or device collected from apps, websites, or offline properties not owned by you.

Data Linked to You

Under this portion of the label, a developer must disclose whether any data can be used to identify you. This can include account information or data gathered during regular app use. Anything collected for advertising purposes must also be listed.

Data Not Linked to You

Finally, under this section, developers can clarify when certain data is gathered but isn’t linked to your identity. The most obvious examples are apps that collect usage data, identifiers, or diagnostics.

App Store Privacy Labels: Examples

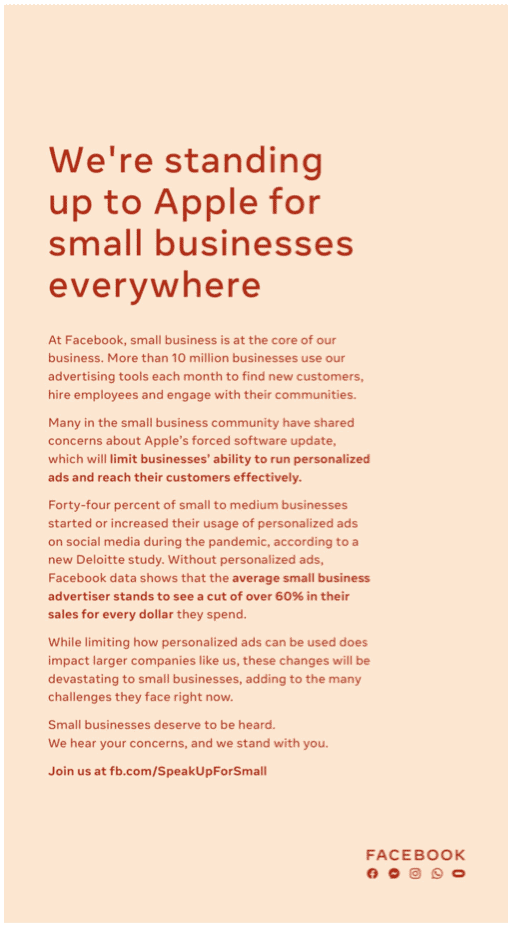

Everyone doesn’t like Apple’s privacy labels. Facebook, in particular, was less than amused and for a good reason. What Facebook’s App Store privacy label shows shouldn’t come as much of a surprise. Companies like Facebook and Google have long collected user data for marketing purposes. Seeing the details in black and white put this collection in more context. Unfortunately, like seeing how many calories are in your favorite dessert, it isn’t pretty. Though Facebook has complied with Apple’s new rules, it made its dissatisfaction well known. In December 2020, the social network put large ads in some of the nation’s largest newspapers criticizing the new rules. In doing so, the company claimed it was “standing up to Apple for small businesses everywhere.” Nonetheless, Facebook eventually complied.

Facebook’s lengthy label in the App Store includes a long list of data linked to a user’s identity that might be shared with third-parties. Details include location, contact information, your photos or videos, search and browsing history, and much more. The collected information could also play a role in product personalization, app functionality, and “other purposes.” Facebook may also use this information for its advertising and marketing programs. The company’s other apps tell similar stories. In early January, 9to5Mac looked at Facebook’s Messenger and compared its privacy label to competitors like Signal, Apple’s iMessage, and even Facebook’s WhatsApp. The difference between each apps’ “Data Linked to You” sections is striking. The short conclusion: Facebook collects lots of user data, as does Messenger. WhatsApp, not nearly as much.

Other Examples

Google, unlike Facebook, has not been quick to comply with the new App Store privacy labels. Of its many apps, Gmail and Google Drive include labels, as do YouTube and YouTube Music. Google Maps, Google Chrome, Google Drive, and Google Photos don’t have labels at this time. Of the Google apps that do have labels, the amount of data collected and possibly given to third-parties is generally much less than what Facebook is doing. However, it still might be too much for some users. In one final example, Twitter also collects a large amount of personal data that might land in the lap of third-parties. General contact information, browser history, location, user content, and usage data are among the items Twitter collects.

App Store Privacy Labels: Final Thoughts

Most of us are probably okay that some user data goes towards advertising or marketing. This is especially true for free apps that depend on this type of collection to make money. The App Store privacy labels no doubt have added some much-needed transparency. In turn, consumers should use this information to decide whether companies like Facebook collect too much information. In turn, these companies, which weren’t necessarily open about their marketing practices beforehand, must decide whether changes are necessary. Ultimately, consumers, not the companies, will be the final ones to decide how much is too much. These App Store privacy labels are a good start, and I can’t wait to see where they go from here. Stay tuned. And if you’re using Android, you can also see which trackers and permissions are lurking behind those apps. Read our article: How to List Trackers Embedded in Your Installed Apps on Android.

![]()